Placing Ernest Hemingway’s To Have and Have Not in the 1930s – an essay by David Gagne

written for LIT 4930 on April 10, 1996

written for LIT 4930 on April 10, 1996

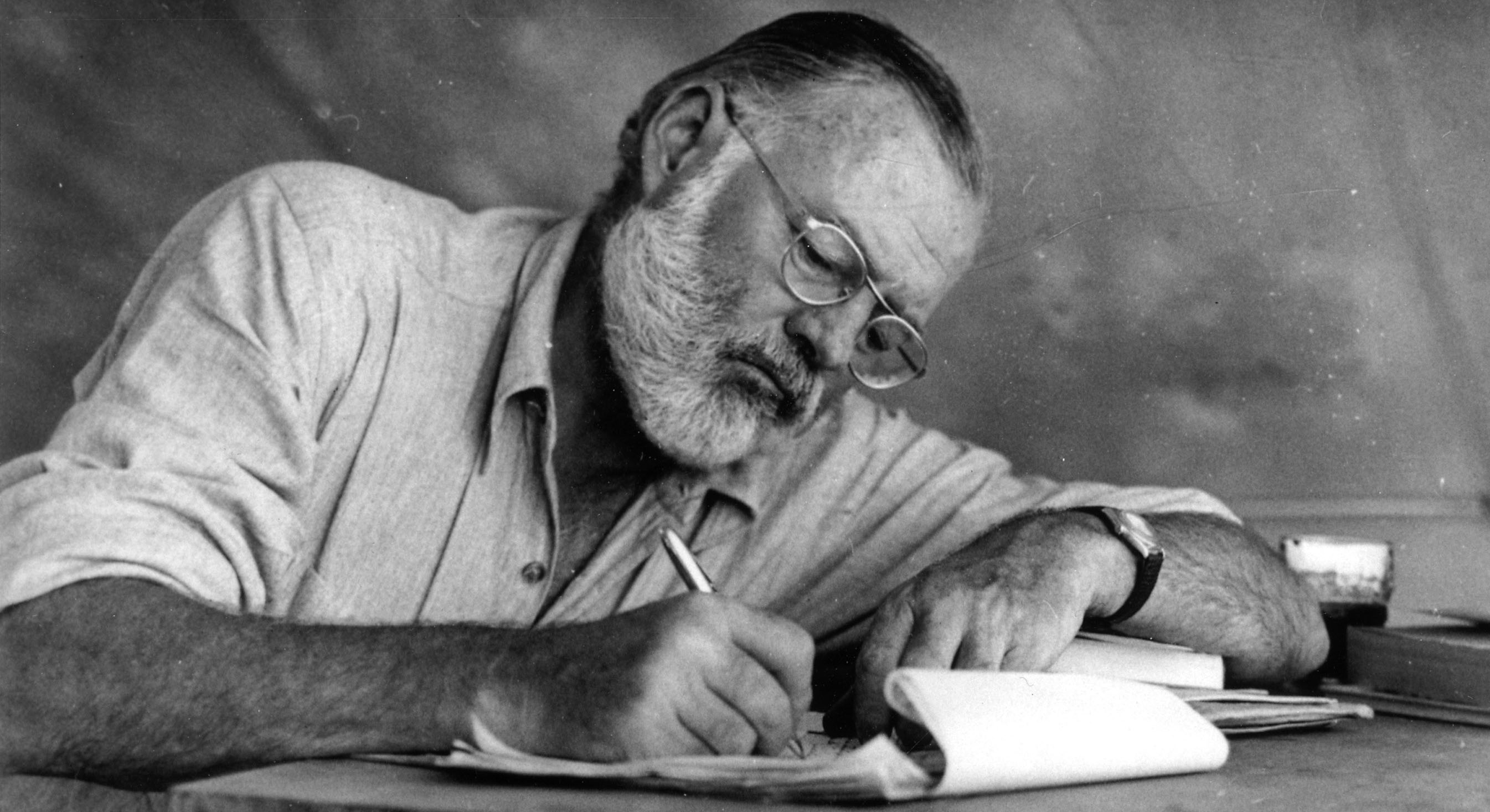

Ernest Hemingway‘s story of a fisherman/sailor/smuggler trying to make ends meet, To Have and Have Not, is particularly well-suited to a discussion of Depression-era literature. Set in the cities and waters of Cuba and South Florida in the early 1930s, the novel delves into not just the psyche of one man struggling to survive through hard times, but also the angst of a world in which the already-thin line between good and evil is blurred beyond recognition. The characters Hemingway represented run the gamut from wealthy socialites to drunken locals and crooked officials. The choices they make because of a society which has abandoned its faith in traditional morals are often not really choices at all, but merely the only apparent avenues of survival.

There are more than a few direct references to the 1930s in the novel. At one point Harry Morgan mentions listening to Gracie Allen on the radio while he recuperates from an adventure at sea. Prohibition gave Morgan the lucrative ability to smuggle alcohol into the United States and its 1933 repeal greatly lessened one of his main sources of income. South Floridian government’s perceived attempts to, “starve [them] out of here so they can burn down the shacks and put up apartments and make this a tourist town,” are typical of a society trying to create income and deal with poverty in the 1930s.

Harry Morgan’s fear of his family’s starving when he can no longer put food on the table is similar to those of many out-of-work Americans in the Depression. Compare Harry’s statement, “I don’t know who made the laws but I know there ain’t no law that you got to go hungry,” with Jeeter Lester‘s comments in Erskine Caldwell‘s Tobacco Road: “My children all blame me because God sees fit to make me poverty-ridden… They and Ma is all the time cussing me because we ain’t got nothing to eat… I can’t make no money, because there ain’t nobody wanting work done.” Jeeter turns to thievery because of his hunger, just as Harry Morgan turns to bootlegging and smuggling.

Hemingway deals with racism against blacks and other minorities as well. The character with whom Harry makes a liquor run early in the book is black. Although Harry addresses the man by his name, Wesley, the narrator refers to him only as, “the nigger,” or, “the negro.” There was money to be made in smuggling illegal immigrants into America in the 1930s, and the Chinese immigrants that Harry is talked into smuggling to America are referred to in a derogatory fashion as “Chinamen” and “Chinks” and they are said to have a foul smell. Morgan makes a point of trying to get rid of their odor before he lands his boat. The pains and deaths of minorities, considered sub-human, are marginalized in the story, not by the author but by the other characters.

Hemingway’s experimantations with the novel form are also notable features typical of early twentieth century literature. To Have and Have Not breaks from the traditional five act dramatic plot sequence of setting, rising action, climax, closing action, and summary. The author, who had lived in Paris, Spain, Mid-Western America, South Florida, and Cuba, wasn’t satisfied with presenting the novel from one point-of-view. No one character narrates the story. The book’s ending is not contained by the standards of time and spatial continuity. Hemingway utilized and sometimes invented these new literary devices to try to push the American novel beyond its limits. Like his contemporary, James Agee, he was creating something which wasn’t supposed to be thought of as art.

The book is divided into chapters, and into three primary parts, each a season in Harry Morgan’s life. Spring, Fall, and Winter are paralleled not with the passage of real time in the story, but with traumatic events which occur to the main character. Hemingway can be read as experimenting with different voices and points-of-view. In the Winter chapters the story is narrated not only by an omniscient third-person, but by Harry Morgan and Albert as well. With the aid of the chapter sub-headings it is sometimes obvious which voice is the narrator’s — “(Albert speaking)” or “(Harry speaking)” — but at other points Hemingway leaves it to the reader to discern which voice is speaking.

Near the conclusion of the novel there occurs a whirlwind tour of the yachts moored in Key West, Florida. Hemingway writes very briskly but with great attention to detail about the snarls and entanglements of the lives of the people living on the yachts. As Harry Morgan is dying, the reader is granted a glimpse into the minds of all those surrounding him. The sequence is very similar to John Dos Passos‘ “The Camera Eye” segments in his novel, The Big Money. The numerous discoveries of the early twentieth century all affected society’s perception of the place of man in the universe. Much like the philosophical and sociological unrest caused by the ideas of Galileo and Darwin, Einstein‘s revelation that time is relative and Freud‘s newly imported theories on the depth and subconscious nature of human conscience were causing quite a stir in the world. These ideas were on magazine covers and were well-known to most Americans. Hemingway used To Have and Have Not as a vehicle for expressing the average American’s fears and uncertainties about these new developments in the human paradigm.

In James Agee’s work Let Us Now Praise Famous Men he writes, “The deadliest blow the enemy of the human soul can strike is to do fury honor. Swift, Blake, Beethoven, Christ, Joyce, Kafka, name me a one who has not been thus castrated.” Harry Morgan, who loses an arm in the Fall, is the 1930s’ literary realization of this statement. Ernest Hemingway’s To Have and Have Not is more than modern American novel. It is a slice of 1930s culture; it is a summary of the decade encapsulated in the story of one man’s rage against a society which has minimalized and neglected him. Harry Morgan is a sharecropper and a flapper, an immigrant and a capitalist. A man who is forced by the socio-economic climate of the times to do evil in the vision of honor, he represents all the characters of the 1930s struggling to continue through hopelessness.

Good website, useful information. thanks!

very usful website the only site i found what i am serching for

Great info, i actually got some answers that i searched forever for in all the other sites..thanks:D

This is one of my favorite books, good work sparky! Its an excellent review, i comend you! HA I RYMED!